[by Kathleen Mulligan-Ortiz]

The late 1960s and early 1970s were a time of great social change. While many people experienced these years as a new spring, a time of intellectual, artistic and personal rebirth, for thousands of young people on New York’s Lower East Side it was a time of increased alienation, anger and despair. Poverty, racism, rampant drug use, gangs, street violence, indifference or hostility from societal institutions – all combined to send the message to Black and Latino young people that they were of no value to the larger society. In addition, the traditional way out of these oppressive conditions – education– was in itself a part of the problem, creating and reinforcing a sense in many young people that they could not learn or succeed. There was a huge drop-out problem in the public schools, not only from High School but increasingly from Junior High School. For those who stayed in school, functional illiteracy was an increasing problem. Hundreds if not thousands of students in Junior and Senior High School were graduating with second and third grade reading levels. Statistics for District One at the time showed that 70% of Junior HS graduates were reading below a third grade level, and that 60% of these young people dropped out of school after ninth grade. Only 10% of elementary and Junior HS students were reading on grade level or above.

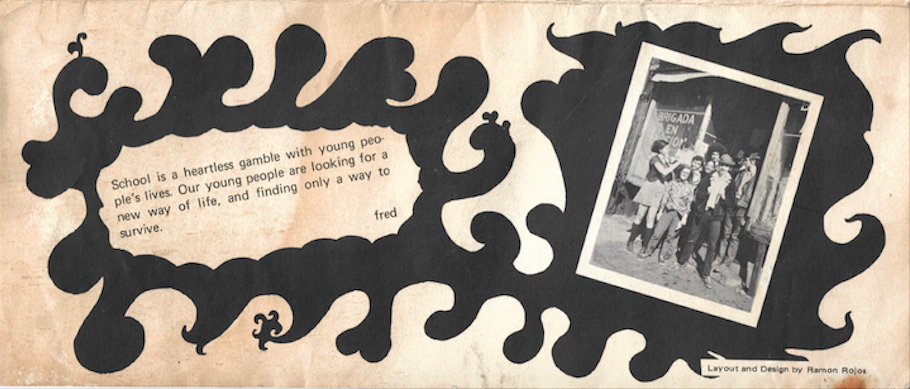

At the same time, there was a core group of dynamic teenagers at St. Brigid’s Church who, supported by two of the the new co-pastors, Dermie McDermott and Matt Thompson, were rapidly developing social consciousness and leadership skills. Some of these young people were doing well in school, others had dropped out or had graduated with elementary school reading levels. But all shared the same conviction: that the growing crisis in education was the result of an educational system which did not respond to the lives and needs of the students, and which actively discriminated against the poor, minority students of the Lower East Side. They believed that the crisis was essentially a human and spiritual problem, one of not recognizing, honoring or valuing people’s history, culture, and unique contributions and potential. Fred González, one of the teens, summed it up: School is a heartless gamble with young people’s lives. Our young people are looking for a new way of life, and finding only a way to survive.

In 1971, a group of St. Brigid’s teens began meeting with a number of adults in the community to develop a response to this situation. Meeting in each others’ apartments throughout the winter, this group – Fred and Elsie González, Ivan Calcaño, John Baez, Chris Wrobleski, Neysa Pabón, Gil and Kathy Ortiz and Matt Thompson – developed a vision for a unique alternative school. It would be open to all young people ages 13-18 who, for whatever reason, had dropped out or been kicked out of local schools. It would be a community school, with teachers as well as students living on the Lower East Side, and with close ties to other neighborhood groups. It would be small, with a high ratio of teachers to students, so that each student’s needs and interests could be met. It would be bilingual, with an emphasis on developing social and cultural consciousness. Above all, the heart of the school would be the relationship between the students, teachers, parents and community; relationships which would extend beyond the structure of the school and which would make it possible for real learning and growth to take place for all. In short, it would be a revolutionary project.

[click to open]

By Spring of 1971, the group decided to have Kathy begin by teaching a few students in her apartment. At the same time, Matt Thompson arranged to send Iván and Johnny to Cuernavaca, Mexico to attend a radical educational Institute for a month. They returned transformed, and gave new impetus to the plans to start our own school. That Fall, Matt officially got the school off the ground by committing St. Brigid’s to pay a small salary for one teacher. We found a home in Brigade in Action, a program begun by Dermie under the auspices of the anti- poverty program, and Kathy began with three students and the frequent presence of the St. Brigid’s group as part-time teachers, part- time students, and full-time enthusiasts and thinkers. In addition to space, Amelia Dávila, Director of Brigade gave us Lucy González, one of her staff, as a teacher; St. Brigid’s ―loaned us Julie Cruz as an invaluable secretary (later secretary-treasurer). We had begun, although we did not yet have a name; and we quickly began to grow.

That same month we wrote a proposal seeking funding and sent it to a number of foundations. We were invited to visit the Edward E. Ford Foundation in Connecticut, and Gil, Kathy and Elsie González made the trip.Thanks in large part to Elsie’s eloquent passion, we were given a grant of $27,000 and immediately hired Chris, Neysa and Roberto to join the staff.

By the school year 1972-73 we had a full contingent of students and staff, and were fully realizing the early vision for the school. Learning was taking place in many ways, in groups that were small and flexible. Some students were studying for their GED, others working on improving their skills to be able to succeed in public school, and still others were learning to read for the first time. Over the years, teachers were innovative in creating curricula and materials that would be relevant to the students’ lives, teaching classes in Black and Puerto Rican History, Urban Youth, Oral Interpretation of Literature and Music, as well as basic reading, writing, math, science. For non-readers, we used or created materials developed for older, urban young people. We taped the students’ stories, transcribed them and used them as primers. Students and teachers met together to plan classes. The community, the city and the world beyond were all resources. Teachers and students went to museums, plays, art shows, films. We went to political demonstrations, went ice-skating, played in the snow in Central Park, explored Chinatown – all close by, but worlds away from our students‘ experience. For several years we spent a week in the Spring, thanks to the intercession of Fr. Birkle of St. Brigid’s, at the St. Vincent de Paul Camp, where our tough students would not want to leave the cabin after dark. The community also came into the school, as many people contributed their time and talents as volunteers, teaching art, film-making, science, health, yoga and other classes. Many agencies helped by providing us with additional space, material and resources, and by referring students to us.

By 1974, the school had expanded to meet the needs of the wider community. We now also had a night school, teaching ESL and GED to adults, in both English and Spanish. The classes, taught by Gil, Kathy, Roberto and Lucy, were extremely successful, enrolling over 100 adults. But the primary focus, and the heart of the school, was always the young people. Keeping the school going was never smooth or easy. The Edward E. Ford Foundation helped us with grants for several years, and we received small grants from other groups, But we never had enough money to fully develop the school – even though our teachers worked for subsistence wages. We had a constant struggle for space. We had outgrown Brigade and had little money for rent. As a result, we often worked in deteriorating storefronts with poor plumbing and little or no heat. Our students were often depressed or angry, acting out in the school their rage and frustration with society. Many young people, especially those referred by the local schools, were hostile and defensive. There were some who, usually because of drugs or gang involvement, could not adapt to the school, but the majority would eventually relax and begin to thrive, sometimes within a very short time. Students who had been kicked out of school for destroying property,setting fires, attacking teachers, would become cooperative learners. Their explanation was always the same: The teachers here treat me like a person. We also had students who had been classified retarded and dangerous; we would find after a few months that they were neither – rather that they had been seriously victimized by the inhumanity and mindlessness of the bureaucratic system.

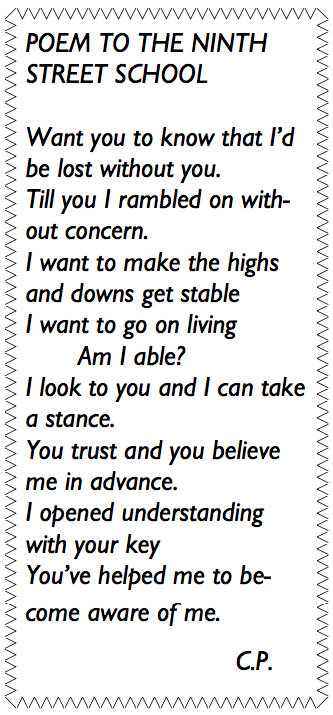

Our goal throughout the years remained the same: to provide a safe place where each young person was seen, heard, respected and valued, and to create an environment where each student could learn and grow academically, personally, and as a member of a community. And always, always, our relationships with each other, the building of community and family, was the essence of the school. We did not always succeed. The damage that had been done before the students came to us was deep and early; the lack of role models and family support, the pull of drugs and of the street – all had an impact and, in later years, claimed the lives of too many of our students. But many more learned, grew, got their diplomas, changed their lives.

Our goal throughout the years remained the same: to provide a safe place where each young person was seen, heard, respected and valued, and to create an environment where each student could learn and grow academically, personally, and as a member of a community. And always, always, our relationships with each other, the building of community and family, was the essence of the school. We did not always succeed. The damage that had been done before the students came to us was deep and early; the lack of role models and family support, the pull of drugs and of the street – all had an impact and, in later years, claimed the lives of too many of our students. But many more learned, grew, got their diplomas, changed their lives.

In 1981, Multi-Service Center 4 (Brigade in Action) was disbanded and with it, the school’s primary source of revenue. The Ninth Street School officially closed, but continued in the hearts and minds of the many teachers, students and volunteers whose lives had been affected by it. It is impossible to mention the names of all those who worked in the school but a few must be mentioned: Kathy and Gil Ortiz started the school and taught in it until 1979 and 1980 respectively; Roberto Méndez became the school’s Coordinator and Director of Brigade for its last year; Chris and Neysa Wrobleski and Lucy González were key in the beginning years; Diane Gallagher, James Wright and Don Pollock were the teachers for the last 4 years. Iván, Elsie, Julie, Margie Rodríguez, Mary Sheehan, Ani Parilla, Awilda Rivera, all helped immeasurably, as did many incredible volunteers, among them: Vincent Fanelli taught science; Ellen Weintraub reading; Helena Kissaris, Babs Jackson and Henry Fiol taught Art; Terry Spallone health. The school could not have grown and flourished without the support of the Board of Directors, especially Freddy González, its first Chairperson, Matt and Rita Thompson, Dermie McDermott, Diane Churchill, Fred and Ethel Good, Elsie González, and many others. We thank them all.

HOME ~ ABOUT ~ A LOISAIDA STORY ~ FEATURED ARTIST ~ BOOKS ~ POETICS ~ PHOTO GALLERY ~ VIDEOS ~ LOS MAESTROS ~ LINKS ~ EVENTS ~ CONTACTS